"Sinners" in the Hands of a Happy Historian

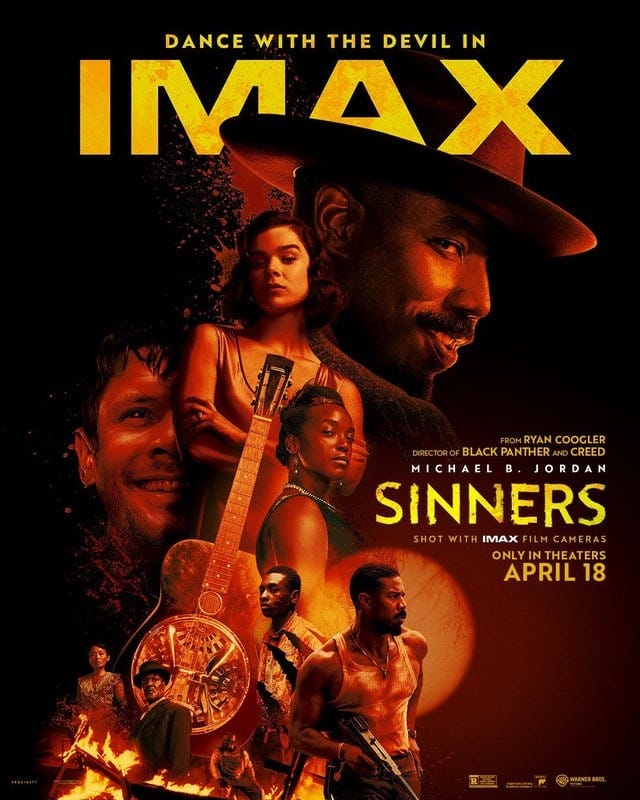

Being the "Economic and Historical Consultant" for this fantastic film turned out to be a great gig.

It’s beyond rare for someone who traffics primarily in things that have already happened to feel the need to issue one of these, but just in case you’ve spent the last month bemoaning the spotty cell service on Pluto and haven’t seen this movie or managed somehow to escape the nonstop chatter surrounding it, here we go: “SPOILER ALERT!!” (Damn, that felt assertive!)

I have spent countless off-the-books hours in consultation with documentary film makers of all stripes, and even popped up as one of the dreaded talking heads in a few of their productions. In either case, my role was to address broader questions of interpretation or historical perspective as opposed to focusing more on granular detail.

Then, about a year ago, an email arrived from producer Sev Ohanian at Proximity Media concerning my potential interest in serving as an “economic consultant” on a major motion picture project set in the Mississippi Delta in the 1930s. Such creds as I boasted for this assignment came down to my book, The Most Southern Place on Earth: The Mississippi Delta and the Roots of Regional Identity, which made its print debut more than thirty years ago. At first, I had the uneasy sense of being drawn into uncharted waters in a leaky rowboat. Yet, knowing full well that my late muse and role model Kinky Friedman’s immediate response to the proposition before me would be” Why the Hell Not?,” and, not about to let the ol’ Kinkster down, I signed on for what would turn out be one of the best rides I’ve had in a long time.

There are ways in which a writer of fiction rather than history might have had a better feel for what lay in store for me because, by its very nature, their craft, not unlike like that of film makers, asks them not so much to document and explain what happened as to give their audiences a sense of what it was like to be there when it did. In this, they enjoy a certain “creative license” seldom granted historians—which is not to say that some of us don’t indulge ourselves in a bit of it from time to time. Still, be it literary fiction or film, there are also scenarios where scrupulous attention to historical detail is (or should be) a must. Writer/Director Ryan Coogler was known for his thorough research into such detail well before he launched the “Sinners” project. Yet his disclosure that his film’s portrayal of life in Jim Crow Mississippi draws on the accounts of elderly relatives who experienced it firsthand may suggest that he had even greater incentive to get things right in this instance.

To that end, my first assignment was to estimate how much it would have cost the fresh-from-the-Chicago-underworld twins “Smoke” and “Stack” Moore to buy the old sawmill that was to be transformed into a juke joint. Although the twins themselves are flush with mob cash, The film was set in and around a Clarksdale, Mississippi, that was still in the merciless grip of the Great Depression in 1932. As it turned out, my assignment required me to demonstrate just how “merciless” that grip truly was. At the risk of venturing into the realm of “T.M.I.,” I determined at the start that I would explain my response to any query in what might prove to be excruciating detail:

As I feared, my intense digging has not produced much in the way of specifics about the value of the building you describe. Although I will keep digging, rather than holding you up further for now, let me venture that the cost of purchasing the kind of building you describe, which I see as weathered and perhaps a bit dilapidated, including an acre of land on which it might sit, would not run more than $200. More than 800 sawmills had shut down in Mississippi between 1929 and 1932. Moreover, as one of the earlier Delta counties to be settled, the timber in Coahoma, where Clarksdale is located, had been largely cleared out well before that. Forest products accounted for only .03 percent of the value of all crops harvested in the county in 1930, and woodlands represented only 7 percent of the county’s total acreage. Although I can’t find the pertinent stats for Coahoma, the value of farm land per acre in neighboring Bolivar County was $76 in 1932; so we can safely conclude that the cost of uncultivated land was considerably cheaper. All things being equal, it also would be to the buyer’s advantage that he was paying cash. The Clarksdale Press Register was replete with foreclosure sales notices during this period, and it’s hard to imagine property selling at anything but cut-rate prices.

After being thanked heartily for conscientiously doing what was asked of me, I was courteously and respectfully informed that for purposes of the plot, the payment for the old sawmill needed to be many times that figure. This episode spoke to the difficulty posed at times by the movie folks’ understandable concern with keeping as many plot details as possible under wraps at least until filming was complete. (Instead of “Sinners,” the working title of the film at that point was “Grilled Cheese.”) Those who have seen the movie will recall that the actual scene of the transaction has Smoke and Stack handing over a satchel containing ill-gotten cash in an unspecified amount but one clearly sufficient to get the attention of the surly white owner, a known Klansman who was unaccustomed to seeing Black people with anything like that much money at their disposal. Even before viewing the scene myself, I realized that I had subconsciously proceeded under the assumption that Smoke and Stack would approach the purchase with an eye to avoiding anything likely to invite more intense white scrutiny and perceptions of them as “uppity” and eager to subvert the prevailing Jim Crow order. Yet, after gaining a better sense of them and what they were about as the film unfolded, I understood that the swagger, not to mention the swag, they brought to the transaction was likely calculated to set local white racial enforcers back on their heels at least long enough for the twins to get their enterprise up and running. Thanks to the enthusiastic involvement of a truly on-the-make Chinese couple, this part of the plan was brought to fruition without white involvement of any sort. (To my mind, one of the big victories for authenticity in the film came in the couple’s pure-Delta and hence exceedingly “un-Chinese” accents, which accords with all my conversations with Delta residents of Chinese descent.)

The twins’ formidable array of firepower, comparable in scale to the huge stash of purloined firewater that they also bring with them from Chicago, indicates that they are fully aware that a violent reckoning with those zealously violent guardians of Jim Crow can be forestalled for only so long, which in this case turns out to be less than twenty-four hours. Yet though Smoke ultimately leaves dead bigots stacked up like cordwood after repulsing the Klan’s attack, his and Stack’s dream has already been reduced to ashes at that point. Well before a crew of menacing Irish minstrels shows up to turn the dancing fools in the juke joint into the walking dead, the results of the twins’ bold experiment what amounts to a form of communal Black capitalism is foretold in the exchange with the very first customer of the evening, an old sharecropper who is unable even to come up with the full fifty cents required of him for a slug of moonshine. He offers to make up the difference with a piece of plantation “scrip,” issued by his white landlord as an advance against his crop earnings and redeemable only in goods available at his plantation’s store or “commissary.” I confess to feeling particularly invested in this scene because I was tasked with figuring out the appropriate charge for the moonshine. I also pronounced myself deeply skeptical of the scrip being accepted as even partial payment in any transaction beyond the plantation where it was issued. Notably, in the film, Smoke and Stack find themselves at odds on this question as well.

I would never even pretend to take credit for contributing to any of the film’s many strengths, but I admit to taking just a smidgen of vicarious satisfaction in New Yorker critic Richard Brody’s commendation of Coogler for writing “‘Sinners’ in dollars and cents.” The disagreement between Smoke and Stack over whether they should be in the habit accepting scrip under any circumstances is actually moot in that, at some point, a significant share of the clientele on which the financial survival of their establishment depends will be unable to pay them any other way. Anyone who has studied the inner workings of the Jim Crow system closely, much less experienced it from the inside, understands that its most elemental premise was that Blacks must remain economically dependent on whites. Had I not known better, after reading Adam Serwer’s cogent and forceful argument in The Atlantic that “The Jim Crow Economy Is the True Horror in Sinners,” I would have sworn that he had been reading my correspondence with the film’s producers.

Queried about what sort of gambling one might expect to encounter in a juke joint of that era, I emphasized craps, because of the relatively low stakes. Pressed for what card games would be most likely, I suggested some version of Five Card Stud. I also noted that while something known as the “Georgia Skin Game” was popular so long as there was enough money in hand, its lightning-quick pace with multiple participants often placing multiple bets per round invited cheating and the violence it might precipitate. Inferring from the question that gambling might be more central to the plot than it actually proved to be in the film, I felt obliged at this point to offer a predictably stern reminder about just how seasonal, not to mention meager, the actual cash earnings of a Delta sharecropper stood to be in a given year. Between Christmas—or shortly thereafter—and mid-fall, the sharecropper generally stood to have little or no truly disposable income beyond what he could scrape up by doing odd jobs on the plantation, such as mending fences, cutting wood, or when fall arrived, picking cotton on his landlord’s acreage at 60 cents per hundred pounds. For this reason, the primary gambling season in the Delta was typically confined to late fall, after the cotton had been picked and sharecroppers had settled their accounts with the planter. Connecting Chicago and New Orleans, the legendary Illinois Central Railroad that carried so many Blacks out of the Delta over the years was also a pipeline of information about happenings affecting those who stayed behind:

Word of a particularly good crop year in the Delta spread quickly through a network of professional gamblers stretching from Memphis to Chicago and beyond. Heading South, they timed their arrivals to coincide with the time when the first real cash of the year, beyond a few dollars here and there, would be burning the proverbial hole in the sharecropper’s overalls.

Even then, my role as a pointy-head-for-hire obliges me to add this caveat about just how much cash that might be. It’s important to remember that not only were cotton prices averaging under six cents a pound in the early 1930s, but that the landlord was taking 50 percent of the crop proceeds, plus adding 15-25 percent interest to what the cropper owed him, for “furnish,” i.e., food, clothing, and supplies, all charged against the cropper at “credit prices” that were typically higher than cash prices. In addition, the cropper was on the hook for any medical bills or other unforeseen expenses his family might have incurred during the crop year. By way of a single example, based on crop yields in Coahoma County and prices at around $.06 per pound in 1932, a sharecropper farming ten acres stood to produce a cotton crop worth roughly $524, half of which would go to the landlord off the top, leaving the cropper with $262, minus all the aforementioned charges (with interest) that might be levied against him. Even if his landlord gave him his strict due after those charges were assessed, his odds of walking away with much more than $50-$75 in his pocket were likely no better than even.

This is not to say that it was impossible for the cropper to have fared better than the above hypothetical suggests. In fact, no less than “always” and “never,” “impossible” is one of those terms that a historian should use only advisedly and probably not even then, especially when that historian is consulting on a film where a bunch of vampires show up slightly more than halfway in.

More often than not, my reactions to inquiries about particular scenes in the film turned not on what was possible but what was probable, improbable, or at least plausible. A case in point arose with Delta Slim’s story about him and a fellow bluesman who had ventured out of the Delta to the Mississippi “hill country,” only to be hauled in on a vagrancy charge—a common device employed to discourage Black outsiders from tarrying too long in a white majority county. Jailed for three weeks, to their astonishment the two found themselves performing from the jailhouse night after night at the behest of local whites starving for some good blues music. Upon their release, each supposedly received $1,000. The exhilaration prompted by this windfall supposedly gets the better of Slim’s companion. After indiscreetly flashing his wad of cash at the train station, his affront to caste protocol ultimately costs him his life.

This story from the film closely approximated a favorite yarn spun by real-life bluesman and raconteur Robert Jr. Lockwood, involving him and another musician then known as Rice Miller, who would later take to calling himself Sonny Boy Williamson—never mind that this moniker also belonged to a much better-known Chicago blues performer. Regardless of who was telling it, Lockwood’s version of this story struck me as no less suspect than Slim’s. The hard-bitten white masses in the hill counties were known for their particularly virulent hatred of Blacks. What reason would the whites featured in this account have to assure that this sketchy duo with a penchant for mischief left the area with their pockets full to overflowing? Yet I knew enough of the purposes served by Black folktales in the South to understand that it was its very improbability that lent meaning to this story and bolstered its vicarious appeal among Black listeners who could scarcely imagine themselves or any of their number managing to give Jim Crow the slip even for an instant. I conceded as much to Sev Ohanian while explaining how I approached my responsibilities as a consultant:

You are also telling a story, which, while perhaps less plausible than the version I advanced, is certainly a lot more interesting and compelling. I see my responsibility as advising you on what would seem plausible to me in a certain situation and what would not. That this also obliges me to be an old stick-in-the mud is to be expected. When I signed on to do this, I certainly never imagined that my take would be regarded as anything more than advice. You guys are the ones making the film, after all.

Happily, this arrangement seemed to work out just fine for all concerned. With the film now tearing it up at the box office and even the most hard-nosed critics going all in with their superlatives, I revel in its success, however trivial my contributions to it may have been. More importantly, I want to thank everyone responsible for giving me the chance to take on perhaps the most challenging, intriguing, and ultimately satisfying assignment of my checkered post-retirement career. I came away with a much greater appreciation of how hard it is to do what you do and grateful for the sense that what I do can be relevant and instructive to a far bigger audience than I could ever have imagined.

P.S. Thanks for steering me in the right direction on this one, Kinky. Rest assured that I will continue to seek your spiritual guidance in all such matters.

Behold below: My pathetic effort to promote myself as the next great pop culture icon.

Fascinating reading Jim, thank you. I’m obsessed with the detail that has gone into making the movie so authentic. The whole team seems to have been on a mission to produce a livery work that is entertaining without being inaccurate. How wonderful to have been part of that team in a movie which in itself will go down in history.

What a wonderful read. As a 3 time viewer of the film and a retired prof of english lit, i was delighted with your commentary, much more interesting than many of the prevailing “lit crit” analyses. THANK YOU